Any writer can tell you rejection stories all the live-long day, even famous ones, because before they got famous, they delt with disappointments. Or I might be stretching a little. Maybe famous writers could only give you half a day’s worth of rejection stories. I could go all day and then some. Maybe as much as a week. But I promise not to do that. It would bore you, and me. A writer just has to accept those rejections and move on. No looking back in anger (though maybe a little mild irritation can be forgiven).

So, I thought I might focus on the positive and tell you about a few highs, one where I’m jumping up and down in my kitchen and another where I quickly get over a minor, and rare, argument with my wife Rhonda. Then, just for balance, mind you, I’ll end with a low that makes me laugh now.

The first story isn’t about an acceptance, but it sure felt like some much-needed validation early on. I’d only published about three stories at the time. It was the spring of 1994, and I was teaching at Clemson University with my friend and poet Rick Mulkey, who I’d known since grad school at Wichita State. We had the writer Robert Morgan coming in to do a reading, and Rick was in charge off squiring Morgan around and taking him out to eat before the reading. At this point, Morgan was already considered one of this country’s finest poets, and he’d begun to publish fiction too, a couple of short story collections and a new book of novellas. He hadn’t yet published his novel Gap Creek, which became an Oprah Book Club pick. So, after going out to eat, Rick and I take Morgan to the auditorium where the reading will take place to check it out and make sure everything is set up properly. While we’re there we’re carrying on with conversation, and somehow, I’m not sure exactly how, the topic of conjuring and witch doctoring comes up. I know. Strange. It’s not a likely topic, is it? Not like, oh, say, the latest episode of Friends (remember, this was the 90s). I do remember that I wasn’t the one who brought up the somewhat unusual subject. Probably it wasn’t Rick, either. So it must have been Bob. Then I remember Bob pausing and saying, “You know, funny, I just read a story about a conjure woman.” I asked him where he’d read it. “I’m not sure. I think it might have been in the Sewanee Review,” he said, naming a really good literary journal. “Could it maybe have been in Shenandoah?” I asked. His face lit up with recognition, and he said, “Yes, that is where I read it. Did you read the story, too?” I hesitated for a moment and said, “Well, actually, I wrote it.” He seemed quite surprised, just as I’d been surprised that anyone had read something I’d written, especially Robert Morgan. “It’s a great story,” he said, and hearing those words was quite a high point, which I still recall fondly from time to time.

I’d also published an earlier story in Shenandoah the year before, one called “Jeremiah’s Road.” So one summer night while I’m home alone in my duplex apartment in Seneca, South Carolina, my land line phone rings in my kitchen. It’s a land line because that was all we had then (and as far as I’m concerned, it was damn well all we needed). When I answer, I hear a voice I don’t recognize, and the male caller asks if I’m me. I tell him I am. Turns out it’s Dabney Stuart, the editor of Shenandoah, and I’m thinking, Why is he calling me? He says, “I just want to congratulate you.” For what? I’m thinking. So that’s what I say, with, I’m sure, a hopeful and expectant tone in my voice. “You haven’t gotten the letter yet?” he says. Now I’m thinking, What letter? So that’s what I say. Now he seems a bit flustered. “I thought for sure you would have heard from them by now.” He pauses a moment. I suppose long enough to open the bag so the cat can crawl out of it. “The story of yours we published, it’s going to be included in the yearly O. Henry Prize Stories collection.” So here is where I begin literally jumping up and down in my kitchen and saying, probably in a loud voice, “You’re kidding! You’re kidding!” Dabney assures me he’s not.

Okay, one more happy story, and then one of those soul-crushing disappointments, of which there have been more than I’d like to say. This time, it was winter, and the day was not going well. Rhonda and I had been arguing about something of which I have absolutely no memory, which tells you how important it was, but, at the moment, it was important, and I was in a foul mood. Rhonda had gone out into the backyard to do something—I didn’t know what—so since it was about time for the mail to have run, I figured I’d go check it. Writers of a certain age will remember how obsessed we were with the mail, and I mean by actual, not virtual, mail. Opening up that box by the door or out by the street was nothing to be taken lightly. It was an act that could bring agony or joy. You were likely to find a return self-addressed, stamped envelope written in your own hand that contained the story you’d mailed out four months earlier. Or maybe, just maybe, you’d find a letter-size envelope from a journal where you’d sent a story, and as you opened it, you could hope that the journal had taken your story, which they probably had. Those physical letters of acceptance are a thing of the past now, and I have to say, an e-mail acceptance does not compare. There was something special about the tactile experience of opening a letter that contained good news.

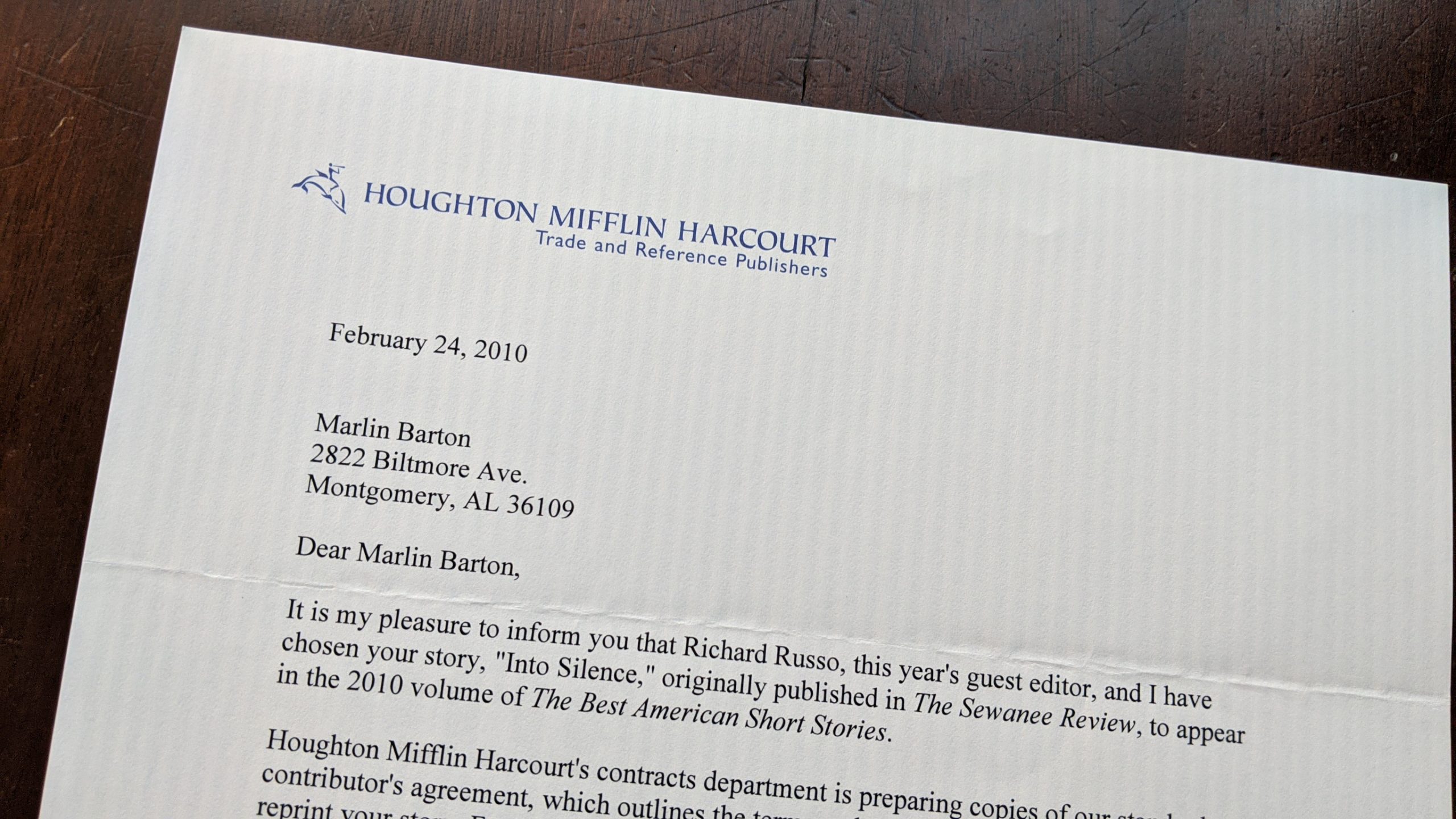

So on this day, an odd letter was waiting on me. I saw from the return address that it had come from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. And I thought (remember now, I was in a bad mood), Who the hell is writing me from there? I don’t know anybody there. I haven’t sent them anything. Why would they write me? I was highly irritated at whomever had sent this missive. I tore it open and was shocked to learn that a story of mine called “Into Silence” had been accepted for the 2010 Best American Short Stories. Suddenly I was not pissed off at the writer of this letter. If fact, I felt much good will toward her and wished her a long and happy life. I then closed the mailbox and walked around to the backyard, where I found Rhonda coming out of our storage house. She eyed me suspiciously, and I simply handed her the letter. After scanning it quickly, she hugged me quite tightly, the argument disappearing somewhere into the ether of a crisp winter afternoon.

I suppose I’m writing about such moments for a very personal reason. It helps me to recall and hold fast to the celebrations as a bulwark against the inevitable rejections and disappointments. One has to remember that joyous moments in a writing life do come, if one will simply keep at it, weathering the tempests those disappointments create.

And here is one such disappointment. Like I said, for balance. I once sent a very long story, 47 pages—the longest I’d ever written at that point—to a very fine and somewhat slick magazine, though I’m not talking the New Yorker or the Atlantic Monthly here. I knew its length would hurt its chances. But low and behold, one morning while I was finishing up writing for the day, my phone rang (yes, a land line still), and it was the editor of this magazine, whom I’d once met and whom I thought was about to tell me he wanted to publish my story. Why else would he call, right? He did say he loved the story but added that it needed cutting. I told him that since I’d sent it to him, I’d managed to cut it by six pages, and he said he had some ideas about how to cut it further. So he mailed the story back, along with his suggestions, and I managed to cut it down to 35 pages, which was a length he was willing to publish. I sent it back to him with all the needed cuts and dreamed of seeing my story in the pages of what would have been the best journal/magazine publication of my writing life. Much time went by. Much time. Did I say a lot of time went by? And then in my mailbox on some nameless afternoon, I found a manila envelope with my address written in my own somewhat blocked lettering. The editor simply said that they couldn’t use the story after all, and he added that one of his interns had made what he felt were some insightful notations on the manuscript. I took a look. The one I remember, and that makes me laugh now, was in pencil within the margin of a page. He had written show, don’t tell, which is something beginning fiction writers learn early on about creating scenes. Those of you who might be writers know how I read this “suggestion.” For those of you who aren’t writers, let’s just say I read it as being the thing that gets added to injury. Here’s what’s important, though. It’s still a great magazine. And I still want to publish in its pages. So I’ll keep submitting, remembering that a moment of celebration can always happen and never losing sight of just how precious those moments are.

Great read, as always!

Thanks, Judy!

You’re forgiven for the missed month, and I agree with you about phones.

Your forgiveness is appreciated! And oh, to live without cell phones again.

Another good read, Bart! I guess Houghton Mifflin and Richard Russo (one of my faves) knew their stuff, and that “slick magazine” (and the intern) missed a good chance!!

Thanks, Donna. I forgot to add that the story did get taken eventually by the South Carolina Review, and I hope it’ll be in a forth collection of short stories.

You’ve had some excellent highs!

I have, Vicki. Sometimes, though, they do seem few and far between. I sure try to appreciate them when they come.

I remember those self addressed envelopes and watching for the mailman in the afternoon. Thanks for this.

I kind of miss all that, though submitting on-line is easier. Thanks so much for reading the piece.

Definitely worth the wait through June! Enjoyed reading this and appreciate the embedded encouragement to keep at it!

As always, Ruth, thanks so much for reading my blog.