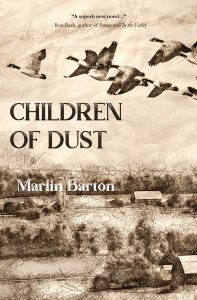

TBR (To Be Read): Children of Dust by Marlin Barton

Work-in-Progress

Sept 13, 2021

Give us your elevator pitch: what’s your book about in 2-3 sentences?

Give us your elevator pitch: what’s your book about in 2-3 sentences?

In 1880s Alabama, Melinda Anderson gives birth to her tenth child who does not live a full day and dies under somewhat questionable circumstances. Melinda thinks her husband’s mixed-race mistress, Elizabeth, killed the child, and Rafe, the husband, thinks Melinda killed him. A century later, in short chapters interspersed throughout the novel, descendants, one white, one Black, who are also cousins, attempt to understand not only what happened but how to relate to one another.

Which character did you most enjoy creating? Why? And, which character gave you the most trouble, and why?

Continue reading the interview at Work-in-Progress.

In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Marlin Barton

Water~Stone Review

Mar 23, 2020

Tell us about your fiction piece “Reading Aloud” in Volume 22. How did it come to be?

What excites you as a writer? What turns you off, makes you turn away or stop reading a piece of writing?

What most excites me as a writer is really pretty simple, and that is fiction that clearly has depth and says something honest about human nature. I also love to read fiction with a lyrical voice, but that voice always needs to be in service to the story. It shouldn’t be there only for show. I tend to learn toward traditional, realistic fiction, but I’m open to stories that break with traditional forms if they don’t sacrifice heart and depth. Stories that strike me as written only for the sake of experimentation turn me off.

What was an early experience that led to you becoming a writer?

Probably my mother reading both Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn to me. I can still hear her voice as she read those books, and I can still recall my deep concern for Huck and Jim as they traveled farther and farther south on the Mississippi River. I knew that was the wrong direction! I also need to mention here that when I was a child I had dyslexia, and my parents learned of a program at the Philadelphia Institutes that could correct dyslexia through a series of “patterning,” where the child actually learns to properly crawl and creep in a coordinated fashion, even when the child has already been walking for years. Eye exercises are also involved. I won’t take the time to explain the theory behind it, but it works. My dyslexia was completely corrected. If it hadn’t been, I’m quite sure I would never have become a writer. But the point I’m trying to get to here is that while I would do my daily crawling and creeping, my mother read book after book to me. I know that words and stories must have crawled into my system and eventually made me want to see if I could write a story. By the way, I finally wrote a story a while back about a twelve-year-old boy with dyslexia called “This Is How Much I Love You,” which I hope will find a good home at some point.

What books, writers, art, or artists inspire you and your work? Do–or have–you had any mentors in your writing life?

Do you practice any other art forms? If so, how do these influence your writing and/or creative process?

I play guitar, though not at a high level. I’ve never played in a band and have rarely played in front of anyone. But when I was in high school something made me want to take lessons, and as my ability grew, my taste in music improved greatly. I began to listen to music and lyrics in a different way, and I think that attention to language helped me move farther along toward becoming a writer.

What craft element challenges you the most in your writing? How do you approach it? What is your quirk as a writer?

I have to be careful with pacing. I can get too bogged down in a scene with too many details. It’s a matter of cutting, and listening to writer friends when they offer a critique. I never send a story out without someone reading it first and responding to it. As for a quirk, I don’t know if this qualifies, but I have a tendency toward writing a formal sounding prose. Maybe sometimes it’s more formal sounding than it should be. But I think I’m trying to capture something that can maybe best be summed by these lines from Emily Dickinson: “After great pain, a formal feeling comes--”

How does the current political climate influence your art or creative process?

I completed a novel called Children of Dust [forthcoming in 2021 from Regal House], which I’m now fine-tuning a bit, that’s set in the 1880s in rural Alabama. It’s largely about race, and I’ve written it from the point-of-view of two white characters and one who is mixed-race. I’ve tried to be very careful how I’ve dealt with the material because race is, of course, such a volatile topic. But this book is something I felt I had to write, and I’ve drawn from a lot of family history/legend/lore.

What are some themes/topics that are important to your writing?

I’ve found over the years that I often write about the nature of guilt, and how characters carry it within them and how they attempt to struggle with it. I’ve also written a great deal about my characters’ capacity for evil. So sometimes my stories use violence, but certainly not always. I’ve never been interested in writing about a completely evil character, what one might call a psychopath, because those characters are, by definition, one-dimensional. I want to write about fully rounded characters who have to struggle with all kinds of human impulses.

What does your creative process look like? How does the environment you are in shape your work or where do you like to write?

What projects or pieces are you working on right now?

I’m about nine stories into a fourth collection, of which “Reading Aloud” is a part, and I hope all the stories in the collection will find as fine a first home as “Reading Aloud.”

Teeth that Bite: An Interview with Marlin Barton, Author of Pasture Art

By Kevin Welch

From the blog Work-In-Progress

March 18, 2015

The magic of the short story seems outshined by the glitz of the best-seller, soon-to-be-a-major-motion-picture, box-office smash complete with new Hollywood cover shot of an actor’s photo-shopped face. I’m not poo-pooing success—who wouldn’t want to see Matt Damon or Claire Danes playing our characters?—just noting that stars falling from the sky and landing on a book’s cover shouldn’t necessarily be the depth of our literary blind date.

Some of the stories that stick with us the most are those finished in a dentist’s waiting room, a lunch break, or even waiting at the DMV (unless you go to my DMV, then just break out War & Peace). Great fiction has heart. It has eyes that bore into you, hands that shake you, teeth that bite. It leaves you with clips and rushes of made up memories, fantasies, something dark, something chilling, and something hopeful, something askew.

Marlin Barton’s latest short story collection, Pasture Art, is his finest work to date. His work leaves lingering echoes that bring the reader back for another go. The imagery is so lush that we know that river, field, and forest as a place from our own past. Barton is a master at telling a story. His mastery shines in this collection of shorts. His stories have heart. And, they have teeth.

I was given an opportunity to ask Barton a few questions about Pasture Art.

When reading Pasture Art, it’s as though we’re in a dinghy drifting on a river that winds through the collection. On the banks, one plot of land cedes to the next and on each a different story. While this is a collection of fictional stories, they feel real and this feeling is given life by the fictional Tennahpush River. Does the river function for you as a character or does its repeated appearance help you blur the lines between fiction and the real world?

I suppose it’s both. The Tennahpush, and the Black Fork River, which is also featured heavily in the collection, do feel a little like characters to me, and they also blur the lines, in a personal way, between fiction and reality. As for their being characters, I hope they come across as living things: they move, they have depth, they have a history that’s older than the people who live along their banks, and I hope they have a presence in the book. For the husband in “Braided Leather” and “Haints at Noon,” the Tennahpush offers aid in a possible escape from slavery, and in “Pasture Art,” it holds a level of danger if you think about the fisherman who end up shooting at the statues of deer at the top of the high bank.

Both rivers are fictional, but they are based on the Tombigbee and the Black Warrior Rivers in Alabama. I grew up in a little community called Forkland, which lies in the fork of the two rivers. I think it was inevitable that rivers would flow through all my fiction, and when I describe these rivers, I see in my mind’s eye the rivers that I grew up swimming and fishing in, but I wanted to give them fictional names to remind myself that I do need to create my own unique world for my characters. I have to add that over the years I’ve submitted stories to the Black Warrior Review, with no luck. It does seem like a writer who’s actually swam all the way across the Black Warrior, and it is a wide river, ought to have some advantage in placing a story there.

Rivers play an important role in your most recent novel, The Cross Garden, and again throughout Pasture Art. Scholars and critiques tend to relate a river to life but your rivers are somewhat darker. Where does this influence come from?

Rivers are life-giving things, I suppose, but life also has its darker side, which fiction must address. I’ve sometimes had my stories and fictional vision, if that doesn’t sound too fancy a term, described in reviews as “dark.” I don’t think of myself as a particularly “dark” kind of person; I try to be hopeful, and I also attempt to reach a place of hope in my fiction, but my stories and novels have often explored my characters’ capacity for evil, which is a theme as old as literature. So I think I’m going about the business of what I should be doing as a writer, and the rivers that run through my stories are simply a part of that. In The Cross Garden, for example, a murder by drowning has taken place, and I try to suggest in the novel that the river itself holds the memory of that act, just as it’s held in the memory of the main character Nathan.

Pasture Art features a number of stories from the female POV. What attracts you to that POV? Is it easier to define the supporting male characters from outside their POV influence?

I have often written from a female point of view. I’m not sure why, and haven’t really thought about it all that much, to be honest. I’m not the kind of writer who has notebooks and notebooks full of story ideas, so when an idea comes to me that seems workable, I try to write it. Sometimes the characters in those stories are male, sometimes female. And sometimes they are of a different race. I think all writers have every right to write from a point of view different from their own. How boring it would be to write only from a middle-aged, white, male point of view.

Your remark about it maybe being easier to define a male character from outside his point of view is an interesting one. In the novella “Playing War,” the main character is female, and I realize just now that I had to, of course, define her husband from her point of view. In many ways, that’s what the novella is about. Their marriage is deeply troubled, and Carrie spends most of the novella trying to decide what kind of man her husband is, including if he’s capable of murder. The way she sees and defines him changes, and I hope the way the reader sees and defines him changes too. In fact, I hope the reader can sometimes see Foster more clearly than Carrie is able, even though everything the reader sees comes through her.

While all stories in Pasture Art stay with the reader long after the book is closed, the collection’s final (and longest) work, “Playing War,” is an intriguing, frightening page-turner. Was there ever a thought this could be a novel?

Not really. I envisioned it as a novella from the start. I’d thought it might run 100 manuscript pages or so, but it ended up running about 70 after I did a little cutting. I’ve never been a writer who experiments with form really, but one of the things I wanted to do in this collection was to try forms I’d never used before. So I wanted to give a novella a shot, and I thought just maybe I had a story idea that could sustain the length required. I also wanted to write a short, short, which was a real challenge. I think Brady Udall’s short “The Wig,” which is one of the finest short, shorts I’ve ever read, inspired me to try my hand at it. I’d also read a couple of volumes of slave narratives taken down in the 1930s for the Federal Writers’ Project, and it was a form that intrigued me. So while the short, short “Braided Leather” is written from the husband’s point of view, I thought revisiting that story from the wife’s point of view, and from a distance of many decades, might be a revealing thing to do, and hopefully each story helps to enlarge the other. Finally, there’s another story in the collection called “Midnight Shift” that’s written from a multiple third-person point of view. I’d always written from either third-person limited or from first person. While the story isn’t true omniscient point of view, it still uses a point of view I’d never attempted before.

If you take “Playing War” and put it opposite “Braided Leather” you have a 50+ page story and a one-page story, yet both have a powerful impact on the reader. When do you know a story is complete?

Here’s the short answer: when it feels right. But that’s a hard thing to know for certain. I suppose to give a kind of technical answer, I’d have to say after the climactic moment has occurred and the conflict has reached whatever resolution it’s going to reach, whether that’s a hopeful, completely satisfying resolution, or not. Stories should not tie up too neatly. Every little thread can’t always be accounted for. But the major issue at work in the story must be addressed and resolved in some way, even if that resolution is more implicit than explicit. The best stories work more by suggestion. They end up giving you a sense of how the character’s life might be changed by what’s just happened to them. By the way, I appreciate your compliment of the two stories you mentioned, just as I appreciate greatly your reading the collection so thoughtfully and wanting to ask me questions about it.

ABOUT KEVIN WELCH

Kevin Welch holds the MFA in Creative Writing from Converse College in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Currently, he works as an instructor at Mt. Hood Community College, Portland, Oregon. He is working on his first novel, Military Dreams.

An Interview with Marlin Barton: Contemporary Reflections from the South

by Elizabeth Glixman

July/Aug 2005

The stories are so exact in their sense of place and time, phrase and voice, they disturb and delight, and make the past as alive as the present. The stories are celebrations connecting us with the living and with those who have come before us. Marlin Barton is one of the most distinctive new voices in Southern fiction.

Robert Morgan, author of Gap Creek, on The Dry Well

Marlin Barton’s short stories have appeared in Shenandoah, The Virginia Quarterly Review, The Sewanee Review and The American Literary Review. “Jeremiah’s Road,” a story from his first collection The Dry Well was included in Prize Stories 1994: The O. Henry Awards. Barton was awarded an Individual Artist Fellowship from the Alabama State Council on the Arts in 1992, and received the Andrew Lytle Prize in 1995. Barton’s debut novel A Broken Thing was published in 2003. A new short story collection, Dancing by the River, is due this month. Barton lives in Montgomery with his wife Rhonda. He is assistant director of the “Writing Our Stories” project, a program for juvenile offenders.

I have often been asked to define the term “Black Belt.” So far as I can learn, the term was first used to designate a part of the country which was distinguished by the color of the soil. The part of the country possessing this thick, dark, and naturally rich soil was, of course, the part of the South where the slaves were most profitable, and consequently they were taken there in the largest numbers. Later, and especially since the war, the term seems to be used wholly in a political sense that is, to designate the counties where the black people outnumber the white.

Booker T. Washington, 1901.

In the 1820s and 30s, the Black Belt identified a strip of rich, dark, cotton-growing dirt drawing immigrants primarily from Georgia and the Carolinas in an epidemic of “Alabama Fever.” Following the forced removal of Native Americans, the Black Belt emerged as the core of a rapidly expanding plantation area. Geologically, the region lies within the Gulf South’s Coastal Plain in a crescent some twenty to twenty-five miles wide that stretches from eastern, south-central Alabama into northwestern Mississippi. The unusually fertile Black Belt (or Prairies) soil is produced by the weathering of an exposed limestone base known as the Selma Chalk, the remnant of an ancient ocean floor.

Allen Tullos, Southernspaces.org

EG Your stories take place in the Black Belt of West Alabama where you were born. There is much history and suffering there. Were you aware of this growing up and how did these aspects of existence affect you?

MB I was actually born in Montgomery, which is a Black Belt city in the central part of the state and the capitol of Alabama, and lived there as a young child, but I grew up and spent what might be called my formative years in West Alabama in Greene County in the very small community of Forkland, so named because it sits in the fork of the Tombigbee and Black Warrior Rivers right above Demopolis, which was settled by French exiles from Napolean’s army.

When I moved to Forkland and spent time in and worked in my grandfather’s general store, I suddenly saw a very different world from what I’d known in the middle class neighborhood where I’d lived in Montgomery. I saw people I’d never seen before, or at least spent any time around. Most of the people who traded with my grandfather were poor, black, and many who were of a certain age had been sharecroppers and had lived on the same “place” for years but were no longer living there since sharecropping had died out with the invention and use of the mechanical cotton picker. Also, cotton, as a cash crop had really given way to soybeans and cattle. In fact, my grandparents owned a small 100 acre cattle farm, and the property is still in my family.

During the time I was growing up there in the 1970s, Greene County was the fifth poorest county in the United States, and the second poorest in Alabama. All the Black Belt counties are poor, and yes, to answer your question a little more directly, I was aware of the poverty around me. I saw people living in tarpaper shacks and wearing old ragged clothes, people who couldn’t read and write or count money. I have to say I felt for these people, but I wasn’t outraged by the way they had to live. I was a boy, and it was just the way things were. But I was fascinated by these people and listened to them and observed them as closely as I could.

I was also very aware of the history around me, mostly through family stories and the very buildings in the community. The stagecoach inn where my great-great grandfather Barton first stayed when he came to Forkland in 1857 was, and still is, standing. The dog-trot style log house he built when he returned home from the Civil War stood until I was in college. The house I lived in all through high school was 150 years old, and my grandfather and father had both been born in same bedroom. Our old family plot lay in the back of the graveyard; to get to it you had to walk down a narrow dirt road surrounded by woods on both sides, and even as a boy I remember feeling as if those woods created a tunnel that I had to travel through to reach the past where my ancestors lay. And when I looked at their names on their tombstones, the stories that I’d been told about them made them come alive in my imagination. It was almost as if I could see them walking around the streets and buildings in Forkland.

As for how I was affected by all of this, I guess it made me want to tell stories.

EG How far back can you trace your family’s roots?

MB We know that there were three Barton brothers who came over from Ireland, via a stay in England for some time, at some point in the late 1700s. One of the brothers settled in or near Durham, North Carolina. We don’t know a lot about the early family because my great-great grandfather Barton ran away from his home in Durham at the age of 15, in 1855, and never returned. So there was a break there, so to speak, in the history because of the break he made with family ties.

EG When did you decide to become a writer?

MB I can’t point to a particular moment when I knew I wanted to write. My parents both read to me as a child, especially my mother. And both my maternal grandmother and mother loved fiction. When I was a child my parents discovered that I had dyslexia. They were told by a doctor that I would never learn to read or write, at least not very well, but they learned of a program at a place called the Philadelphia Institute in Pennsylvania that worked at correcting dyslexia and took me there. Then through a regiment of eye exercises and physical exercises called patterning, my dyslexia was completely corrected; I am no longer dyslexic. What I’m trying to get to here is this: while I did those exercises my mother read to me day after day to make the time go more quickly. She often read from a series of books called “Childhood of Famous Americans.” My favorite book was Francis Marion: The Swamp Fox and I also have vivid memories of her reading Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn. Another great memory is my maternal grandmother, who was from Wisconsin, reading Thomas Wolfe’s Civil War story “Chickamauga” to me in her great Yankee voice, though this wasn’t during my patterning.

All of this reading, and all of the old family stories I heard from my father and paternal grandparents lead, I think, to my wanting to write. Then in college, at the University of Alabama, I had to keep a journal for a freshman English class. I didn’t care about doing this at first, but discovered after some time, and really for the first time, that I liked to write. Then I began to write poetry and took a poetry writing class. I know that I really wasn’t much of a poet, but I still learned a lot about writing, about using language and images and about the power of a single word. I dropped out of school for a while but continued reading, and then became curious as to whether or not I could write a short story. I don’t know where this notion came from exactly, but it came. So I tried my hand at it, took some more writing classes when I went back to school, and ended up going to Wichita State University and got an MFA in Creative Writing.

EG The stories in The Dry Well are about several families living in a rural Alabama town from 1865 to the present. The characters include a young Confederate soldier Rafe Anderson whose son, Phil, (when grown) and he appear in other stories, an elderly poor black man Jeremiah, born at the turn of the century, who appears briefly as a child in “A Shooting,” Aiken Reed, a man confined to a wheel chair from birth, who we first meet in “A Visitor Home” and later in the powerful story, “The Minister,” and Lydia who brings the life of a dead member of the Caulfield-Hitt family to life when mourning the loss of her child. Why did you link these stories instead of writing a novel?

MB When I first began writing fiction I was most interested in stories because I’d always loved reading short stories. And I noticed as I wrote stories early on that they always had rural, small town settings, so I decided to make it the same small town each time. I think Sherwood Anderson’s collection Winesburg, Ohio was a major influence here. Then I began to become more and more interested in the connections between the stories as far as place, character, and time. The Dry Well doesn’t read like a novel, or as a novel-in-stories, exactly, but I hope by the end of the book that a reader has a strong sense of Riverfield, the fictional town where my stories are set, and it’s history and culture and people. I hope the whole is more than the sum of its parts, though I tried to make sure that each part, each story, stood completely on its own.

EG As I read the stories I gradually developed a sense of Riverfield and its inhabitants and also a sense of the physical landscape. Seeing a familiar name appear in a new story or the mention of the location of a building in relation to another (even if in different stories) gave me that “ah ha” moment like I could finally understand how to use a road map and get where I wanted to go. And each story stood alone. It is obvious you reached your goal.

MB Well thanks, I hope so. And I hoped that readers would notice some of those small details as far as landscape and buildings that get repeated. I wanted those details to help pull the stories together more tightly.

EG You graphically depict violence in several of the stories. The murder of the Yankee soldier in the title story of The Dry Well was horrifyingly real and abhorrent but somehow I did not hate Rafe for doing it. He, like other characters, for example May in the “Conjure Women,” has an inner explosive rage or fear that appears at inappropriate times, when there is no real threat. I did not see the violence in your stories as gratuitous though, not like TV dramas where death and blood seem so pointless many times. Are you comfortable writing violent scenes?

MB I try to be careful about using violence because a good writer doesn’t want to be gratuitous. Faulkner, I think, grew tired of people complaining about the violence in his stories and novels and once said that complaining about a writer using violence is like complaining about a carpenter using a hammer. I think he meant that violence is a tool for a writer, at least one tool; it allows a writer to go deeply and quickly, and in a dramatic way, into human character or human nature, granted, perhaps down to the worst in human nature. But it’s a writer’s job to look at all parts of human nature, both the good and the evil. I’ve often written about what I think of as the capacity for evil within my characters. And I do think we all have this capacity. I don’t think we’re all terrible evil people, and I wouldn’t call any of the characters in The Dry Well evil, but the capacity is in all of us (and in my characters), and we best acknowledge it so that we can guard against it. I think Rafe and May are two good examples, and I’m glad that you didn’t hate Rafe for what he does. The key there, I think, is to help the reader understand why characters do what they do, even if what they do is abhorrent and makes us want to turn away.

EG What triggers these characters’ bizarre behaviors, like Aiken Reed biting his sister in the ass?

MB It’s essentially the very worst of themselves made manifest because of anger or fear. And I don’t think Aiken is evil, but he certainly has a capacity for it. And he can be mean as hell!

EG Oh yes, you described his meanness well in “The Minister”:

So they said then, the blacks, that Aiken was a child of the devil. Said a child of the devil always dies in fire. And the old ones are sure that that’s the way he’ll go. I don’t know if he was any child of the devil or not, but he did grow up to be mean. He bit his sister Caroline one time. Bit her when she bent over near his chair. And he’s got big square teeth, too, like a horse or a mule. This was after they were older and had to live in that shack out behind Anderson’s store after they’d had to sell the family house. He tried to kill her once, too. Got one of the little black boys who pushed him around in his chair to hand him his sister’s .32 from out of her drawer, and he tried to pull that trigger with those fingers of his that he can move a little.

EG Do you think people are held accountable for their actions by some higher universal plan or force? Aiken did die a death by fire.

MB What’s more important than my personal religious beliefs is that in the story the townspeople have a strong fundamental belief in the Bible, and this gives rise to the myth that surrounds Aiken.

EG Do you give a lot of attention to your stories’ pacing? They have a slow drawn out feel to them that heightened my interest and made them feel like mysteries.

MB I do think about pacing a great deal. I think all writers do. I hope the stories aren’t too “drawn out” or slow. You want them to move and carry the reader forward, but I’ve always tried to bring to bear a certain emotional intensity in my stories, and hopefully depth. I don’t want my stories to be “quick reads.” I want the reader to become absorbed in them. There’s a line in an Emily Dickinson poem, “After great pain, a formal feeling comes.” That line has a great deal of resonance for me, and I’ve tried to use that idea in stories like “The Cemetery,” which needs to take its time in order to explore what Lydia feels after the death of her child.

I’ve never thought of my stories as mysteries, but I like that you use that word. I think I know what you mean.

EG Tell us about your novel A Broken Thing.

MB It’s also set in Riverfield and concerns the breakup of a family that you see in several of the short stories in The Dry Well, the Anderson family, to be specific. The novel is told in multiple first-person points of view, the voices coming from the principle members of the family: the mother, father, older brother, and younger brother Seth, who’s really the central figure I suppose, and lastly the paternal grandmother. I wanted the fragmented narrative to mirror the fragmentation of the family (really the fragmented modern family), and I wanted to explore all the complex relationships that happen within a family. The shifting points of view helped me do that, and also helped me deal with the various perceptions of the truth among the characters.

EG Author/editor Dabney Stuart commented on A Broken Thing: “Barton includes the dimension of mercy, too葉he mutual forgiveness of failures by family members who, finally, find ways to realize they can’t live without each other. An impressive, uncompromising book.”

MB A nice description. I particularly like his phrase “dimension of mercy.” That’s a quality that I hope I bring to my fiction.

EG The characters you portray are alcoholics, beer guzzlers, thieves, child abusers, child arsonists, poverty stricken farmers, husbands and wives who cannot tell each other their inner feelings, fathers and sons who do not treat each other with respect, animal murderers, and racists both white and black. How do you make the reader like them and where does this sense of forgiveness you hold come from?

MB Lord have mercy, I didn’t realize they were all so terrible! But I think of them, at least the central characters, for the most part, as good people who are flawed like we all are, and, as I suggested before, if the writer can take the reader deep enough into who they are and let the reader see why they do what they do, then there can be compassion and forgiveness for them, and sometimes between them.

EG The forgiveness between people is an exceptionally powerful part of your stories, as in “A Father and Son.”

MB All stories are built around conflict, within characters and between them. I think most writers take their characters into these conflicts and hope the characters can find a way out. You want to try to end with some sense of affirmation, if you can, but you don’t want to force anything. It’s a paradox. The writer creates the characters, but then has to be true to who they are and can’t have them do something they’re not capable of. But when characters do have it within them to forgive themselves or others, that’s a nice way to be able to end a story.

EG A sense of place and tradition “ooze” from your stories. Is this sense of time and place and heritage felt by most Alabamians today?

MB A difficult question that’s hard for me to judge. I think young people today spend way too much time with technology, television, computers, the internet, cell phones, and I think too much technology, or at least too much reliance on it, is dehumanizing. They, young people, some of them and maybe older ones too, need to put down the electronics and learn to listen and connect. But I do think that all people need stories. I think there is a basic human drive for it. Stories, it’s been said, tell us who we are. They help us to see ourselves and understand ourselves. They define us. It’s another paradox. We create stories, but they help to create us, remind us of the best of ourselves and our world. And stories don’t come out of a vacuum. They come out of time and place and history. I do think there are people in Alabama, in the South, and in this country, who care about where they came from and who they are, and it may be a bit stronger in the rural areas, what you’re asking about, where there is still more of a connection to land and place where earlier generations sprang from. If we can get off the interstate and the internet for a little while, those places and people are still there, waiting.

EG When did you become involved in the “Writing Our Stories” project?

MB I started in 1997, at the very beginning. The program was created by Jeanie Thompson, a poet, who is the executive director of the Alabama Writers’ Forum. That first year there was just one class of twelve students at Mt. Meigs, the juvenile facility right outside of Montgomery. I now teach three classes at Mt. Meigs and another writer/teacher, Danny Gamble, teaches a fourth. We also have two classes at each of the Birmingham facilities, Vacca, for boys, where Gamble also teaches, and Chalkville, for young women, who are taught by Priscilla Hancock Cooper, a poet and performance artist. So we now have a total of eight classes and we teach as many as 130 students each year. We also publish anthologies of student work every year from all three of the facilities. We’ve now produced eighteen of them, which are free and available from the Forum. People who might be interested can go to the website, www.writersforum.org, and click on Programs to find out more.

EG Was it hard to motivate your students and how did you begin?

MB I began by having my students read and discuss stories and poems by contemporary writers such as Larry Brown, Steve Yarbrough, Edward Falco, Eric Nelson, and Andrew Hudgins; work I felt they could identify with. Then we worked from various exercises that we created over time (which are now available in a Curriculum Guide), and that are designed to teach certain skills such as simile or personification and that prompt them to write poems and stories, often similar to the ones we’ve been reading. In other words, the way we teach is craft based. The students don’t simply write down their feelings. They learn about form so that they can have something concrete to work with and to give voice and shape to what they feel.

The students take the class by choice, so it’s generally not difficult to motivate them. And they tend to write about, without my forcing them in the least, the difficulties they’ve had to deal with in their lives, everything from drugs and crime to poverty and problems with absent or abusive parents. We feel there is a strong therapeutic component to the program, and when they see their work in print and hear praise for what they’ve written, they’re clearly proud of their work and what they’ve accomplished.

EG Your new short story collection Dancing by the River is coming out in July. Will there be any of the same characters from your first collection in this book?

MB Yes, it’s really a companion volume to the first collection. The stories are all set in the same place and many of the same characters appear. The stories in the first collection essentially move from the past to the present if they’re read in order, and the stories in the new collection are pretty much in the reverse order, present into the past, though that’s a bit of a simplification. One of the ideas that I’ve always been interested in as far as my fiction is the connection between past and present, how one shapes and colors the other. I could have put all my stories set in the past in one book, and all the contemporary stories in another, but I don’t think time divides that easily or simply. I hope the two volumes together have a completeness to them.

The novel that I’ve been working on recently is set down the road a ways, and has none of the same characters. Its setting is also completely contemporary as far as time. I was ready to do something very different.

EG Do you ever have thoughts, even if fleeting, that you would have liked to have been born in another country or time or section of the U.S.?

MB My answer probably won’t surprise you. I sometimes wish that I’d been born in the last half the 19th century, in the community where I grew up, so that I could witness my ancestor’s lives, but then I’d want to come back and be able to write down what I saw.

EG I guess you are a good candidate for a time machine ride. Barring that event, I think readers are grateful that you were born in this century with a gift for writing stories that capture the lives of people, relatives or not, in a way that lingers in the mind after they are read.

MB Thank you, and thanks too for reading my stories and caring enough about them to want to ask me questions.