Next month I’ll finish up my twenty-fourth year of teaching creative writing to juvenile offenders behind the chain-link gate at the Mt. Meigs campus of the Alabama Department of Youth Services. It’s been quite the ride, and I’ve taught students who’ve committed all manner of crimes, some as serious as it can get, but when you’re sitting next to a distressed child who’s doing his best to write about and understand his life in an honest way, you tend to forget about what brought him through that gate. He’s just a kid who has lived a life so trouble-filled, often through no fault of his own, that you think to yourself, How could you not end up here?

I suppose I originally thought I’d do my time, so to speak, at Mt. Meigs for a few years and then maybe (hopefully) become a tenured professor at a university, where I’d teach undergrad lit courses and graduate-level creative writing workshops. And in fact, I do now teach grad-level workshops at Converse College in their low-residency MFA program, but teaching at Mt. Meigs has been the larger focus of my career as a teacher, and I’m grateful for that.

All writers write out of some need or compulsion (or to use a term coined by Barney Fife, compelsion) to examine the world and their place in it and to make sense of and create some order out of what often feels like chaos. That’s true for me, and I think it’s true for the students I teach at Converse, but I think it’s even more true, maybe downright vital, for the juvenile offenders I teach. I’ve had many students tell me that taking the creative writing classes at Mt. Meigs helps them to feel more calm and that they get into less trouble while they’re in the facility because they don’t have the urge to act in destructive ways as strongly as they did before.

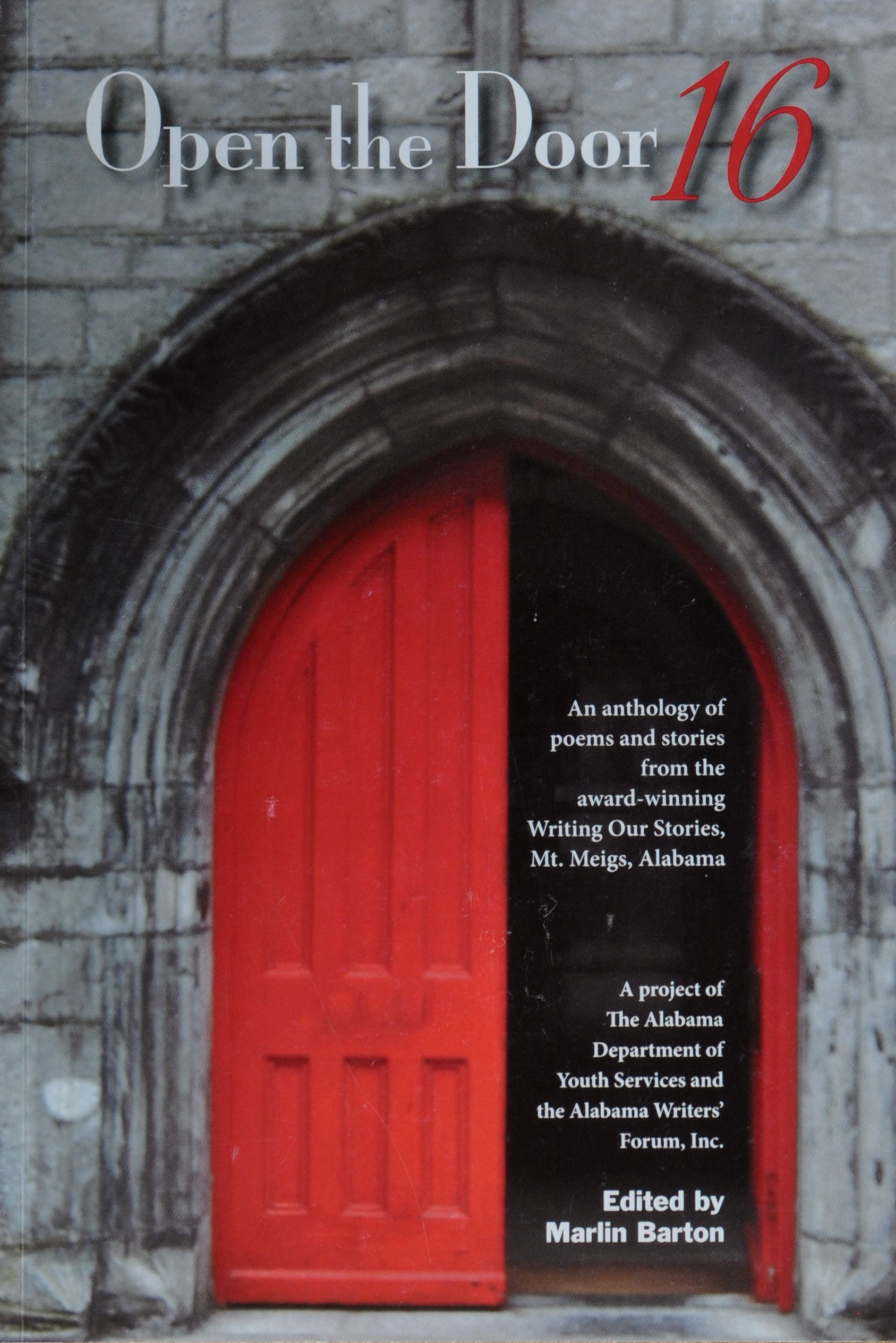

Each fall we publish an anthology of student work called Open the Door, and we have a public reading, on campus of course, where students read their work and hear applause, which they desperately need because so many of them have been told they are worthless. It’s wonderful to see the looks of pride on their faces. Some parents attend these events and many of them have said me, “When we’ve been able to talk on the phone, all my son wants to talk about is the writing class.” One mother, after saying just this to me, paused, seemed to need to gather herself emotionally, and then add, “It’s just made all the difference. I feel like I almost have my son back.” I can’t make any grand claim that the writing my students do saves their lives, but I can’t help but feel it makes a difference that is born of out their great need.

The level of talent and skill I see in my students varies widely, of course, but I learned early on to remain open to even those students whose basic skills are so lacking that I can barely understand what they’ve put on the page. One student, K.H. (because of confidentiality laws, I can only identify them by initials), really stands out in my memory. He was brand new to the class, and when I looked at the rough draft of his first poem, I could not decipher it. So I pointed to the first line and said, “Don’t try to read this. Just tell me what you said.” When he did, I wrote down what he told me. We did this for each line of the poem. Here is a part of what he wrote from the poem “Give Up,” which is included in Open the Door V:

As silence pours through

my walls of pain and hate,

I rest my head on the pillow of death.

My mind floats in the desperate air,

and my back rests on the bed of hell.

Powerful, I think, just as I did when I heard him speak the lines. I learned that day that just because a student’s abilities with the mechanics of the written word are poor or almost non-existent, it doesn’t mean his ability with language is also non-existent. The K.H. thought in metaphor, and it came just as natural to him as walking.

Every year of my twenty-four, I have students who write much better at their age than I ever did. Here’s a poem by one of those students, from Open the Door 21, and while it’s tone is dark, the language, and insight, is so strong that the writing of the poem was nothing short of an affirmative and hopeful act by M.G.

The Radio of Desolation

The radio of desolation bleeds a bleak

liquid of pure blackness

through the speakers into physical existence.

This liquid burns like acid,

bears the smell of a corpse,

and is an unusual shade of black

that strains your eyes to look at it.

The music sounds as if it would like to hold

a conversation, but when you speak

back it ignores you.

The volume knob is hot to the touch,

so when you try to turn up the sound

to hear the music, it hurts you.

The antenna is made of many spikes,

and when you try to get a signal

you have to go through a great deal of pain.

Both of these features only teach you

that trying to connect is painful

and defer you from the thought of companionship.

Static spews from the radio stations

as if it is angry at you for an undefinable reason.

It hurts your ears to listen,

but you bear through it anyway because the sound

of anything is better than the sound of oblivion.

When everything becomes silent once again,

you fall to the side of the radio and listen for more,

hoping, praying, that you hear anything from the radio

to take away the desolation you feel inside.

I don’t feel there are any words for me to add here. The poem speaks not just for M.G.; it speaks for itself.

I’ll offer one other poem by one of the best writers I’ve ever taught, R.E., from my very first year behind the gate. He was a genius, and when I say that, I mean it literally. He tested at the genius level. I’ll never forget him. And I think this poem, from the first Open the Door, and whose form borrows from a poem by the Alabama poet Andrew Glaze, sums up better than I can what my last twenty-four years have been about.

Sitting in the Classroom

Sitting in the classroom

with so many others,

each of us breathing the breath

the other has breathed before,

wondering what there is in here

that keeps us from sitting outside

and breathing the air that the world breathes.

Item:

A blackboard,

the perfect expression of another’s ideas.

White on green.

Chalk on fingers.

Using the eraser to remove

ideas that become less important

when the board becomes full

and something else needs to be expressed.

Item:

A pen

full of black potential

that spills onto the white of a page,

giving me

away from me,

to you.

If you’d like to know more about the Writing Our Stories program, visit writersforum.org/programs/stories.

A moving, insightful, and all together powerful post. Thank you for sharing your talents and experience with the world.

Thanks so much, Lisa. Really appreciate you reading the piece.

Those 24 years’ worth of students have been blessed to have a teacher who so appreciates their worth and has the skill to draw these feelings out. Have you been able to follow up on any of them? To know how the class might carry into later life for them? Thank you for sharing this.

Thanks for your kind words, Ruth. We aren’t able to follow up with students after they’re released, but sometimes we’ve heard from former students many years later and find they’re doing very well. They often say how much the writing classes meant to them.